This year’s cover photo of the WorldRiskReport 2023 was created using artificial intelligence. © Naldo Gruden x DALL-E / Media Company

The WorldRiskReport

Every year millions of people worldwide suffer from disasters in the aftermath of extreme natural events. But whether it be earthquakes, storms or floods, the risk of a natural event turning into a disaster only partly depends on the force of the natural event itself. The framework conditions of a society and the structures in place to respond quickly and to provide assistance in the event of emergency are just as significant. The more fragile the infrastructure network, the greater the extent of extreme poverty and inequality and the worse the access to the public health system, the more susceptible a society is to natural events. Extreme natural events cannot be prevented directly, but countries can reduce disaster risk by fighting poverty and hunger, strengthening education and health, and taking preparedness measures. Those who build earthquake-proof buildings, install and use early warning systems and invest in climate and environmental protection, are better prepared against extreme natural events.

The annual editions focus on a main topic and include the WorldRiskIndex. Since 2018 the report is published in cooperation with the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV) of the Ruhr-University Bochum. The WorldRiskReport should contribute to look at the links between natural events, climate change, development and preparedness at a global level and to draw future-oriented conclusions regarding relief measures, policies and reporting.

Focus: Diversity

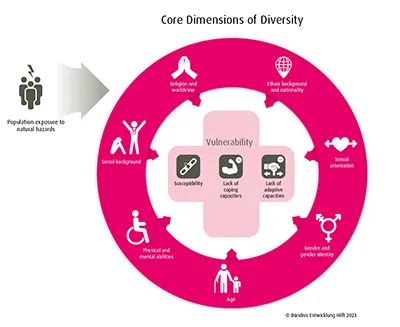

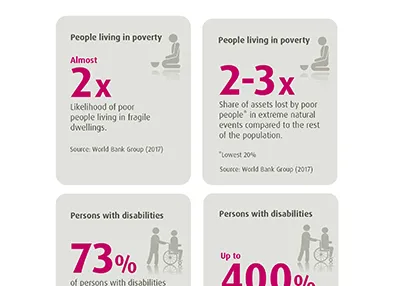

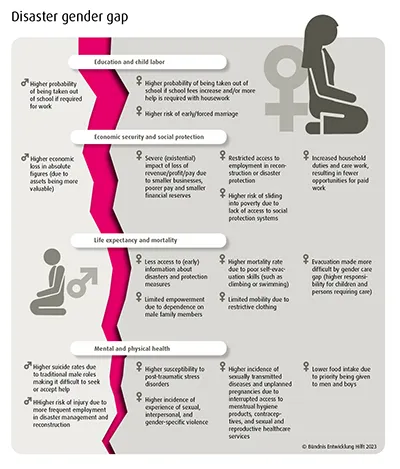

Not all people are equally affected by the impacts of crises and disasters resulting from extreme natural events. Women, children, elderly people, people with disabilities and members of the LGBTQIA* community are disproportionately more likely to be exposed to consequential risks such as (sexual) violence, discrimination, or inadequate access to vital care structures. These increased risks in crises contexts usually root in already existing social and structural inequalities. Often, these do not only refer to one dimension of diversity, but to a combination of different identity features. This intersectionality must be considered in terms of disaster management. However, although an inclusive and diversity-sensitive disaster management is prescribed by law and its importance is widely recognized (by now), its implementation still encounters difficulties.

One of the reasons for this is the lack of comparable data regarding the different dimensions of „diversity“ on a global level. There have been very few attempts to harmonize existing data sets and thus to contribute to a more accurate identification of vulnerable populations. In the event of a disaster, this can compromise the effectiveness of relief and protection measures if, for example, evacuation plans do not consider the special needs of people with disabilities.

To ensure an equitable and effective disaster prevention and response, comprehensive data availability is essential. However, vulnerable populations must also be actively involved in disaster management and key decision-making processes. This requires careful planning, resource allocation and an increasing awareness regarding the specific needs of and challenges for different populations.

Children in the village of Hashim Rustmani in the Pakistani province of Sindh. © medico international

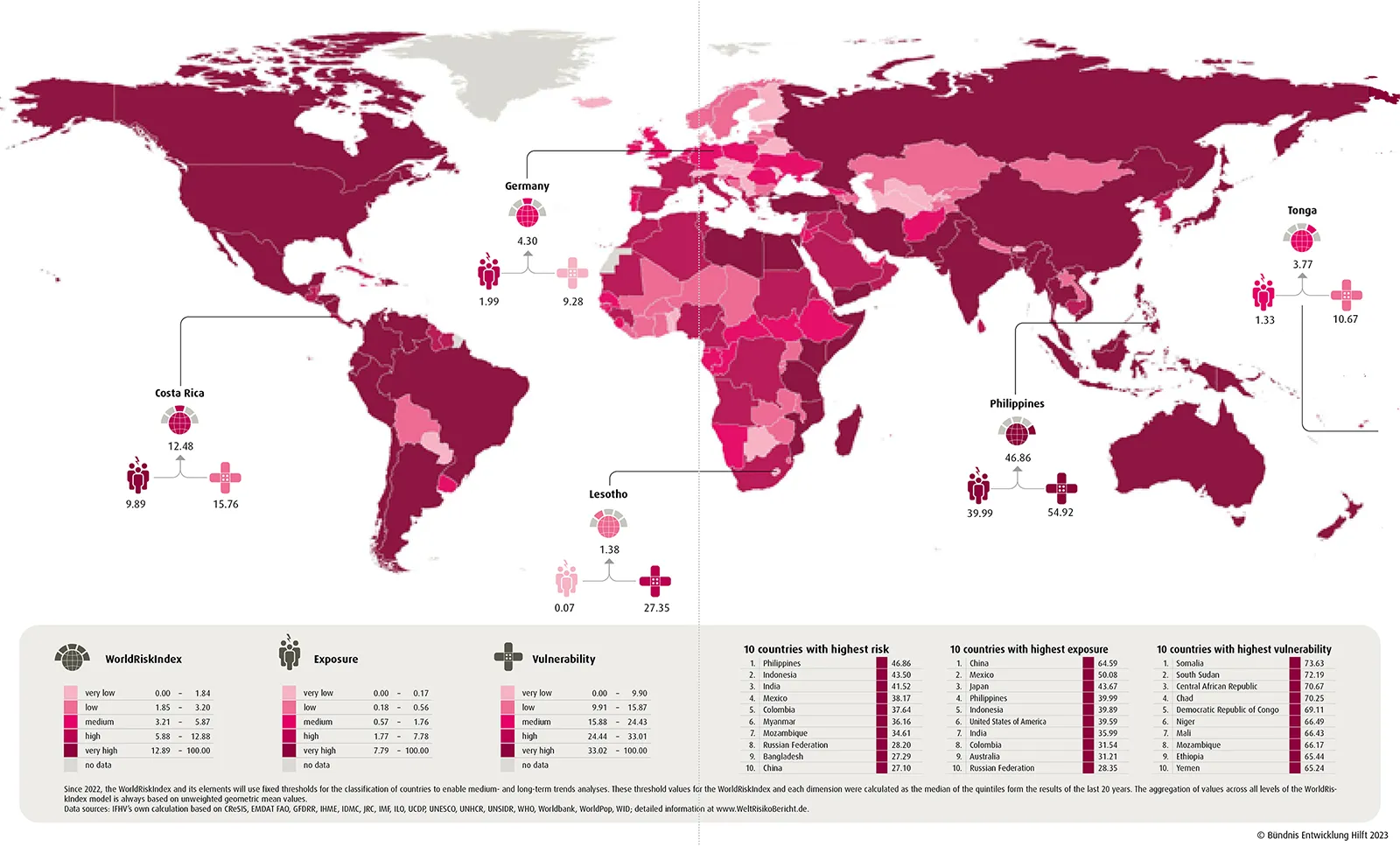

WorldRiskIndex

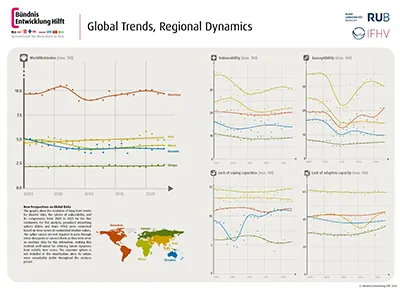

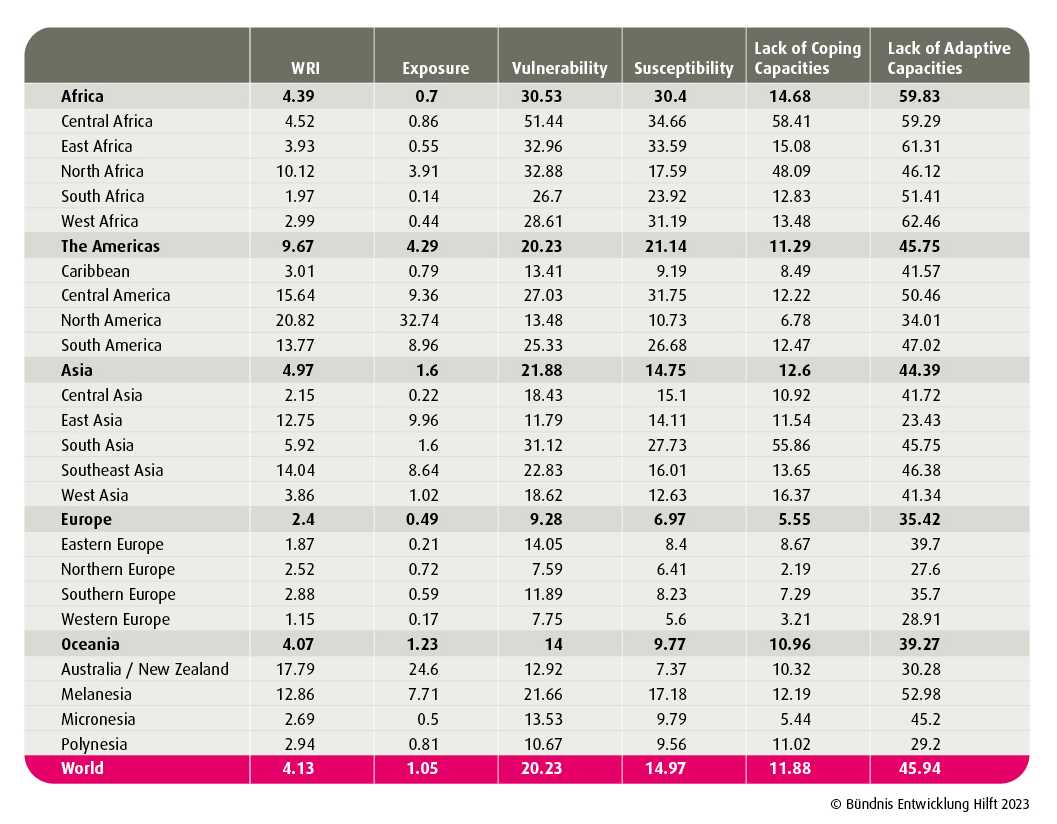

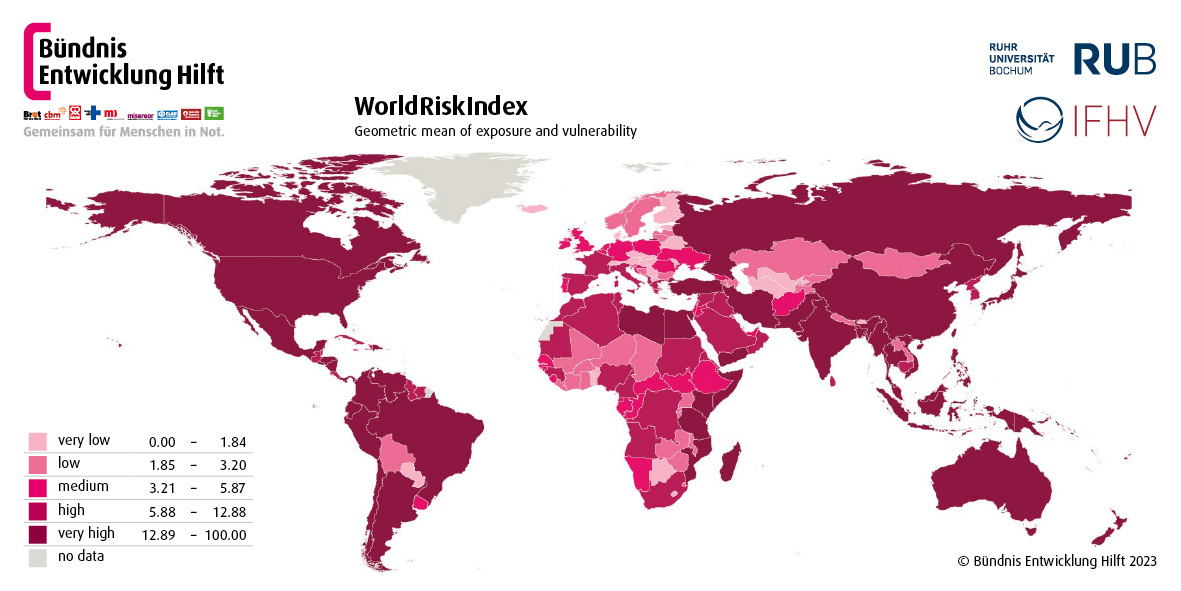

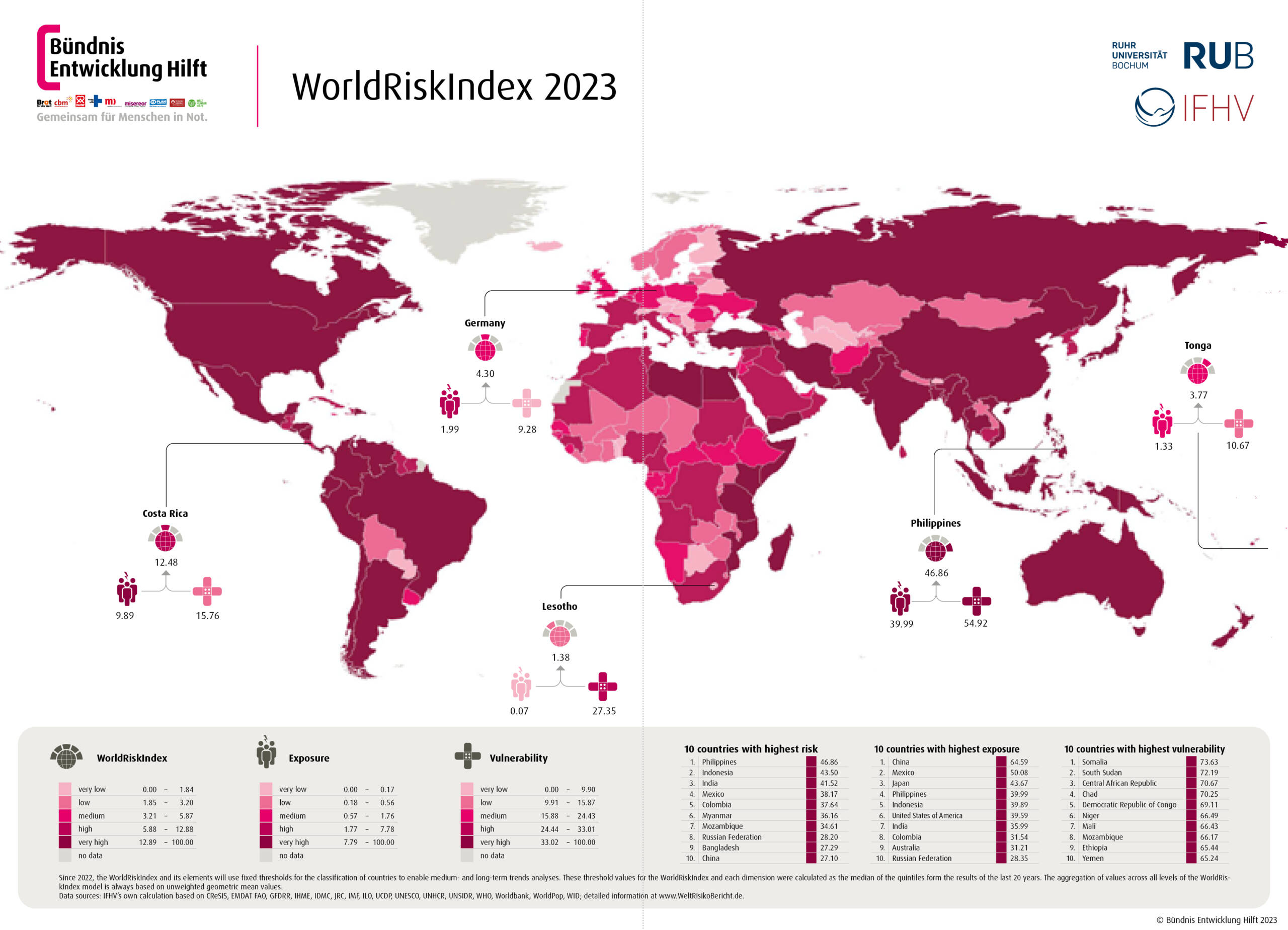

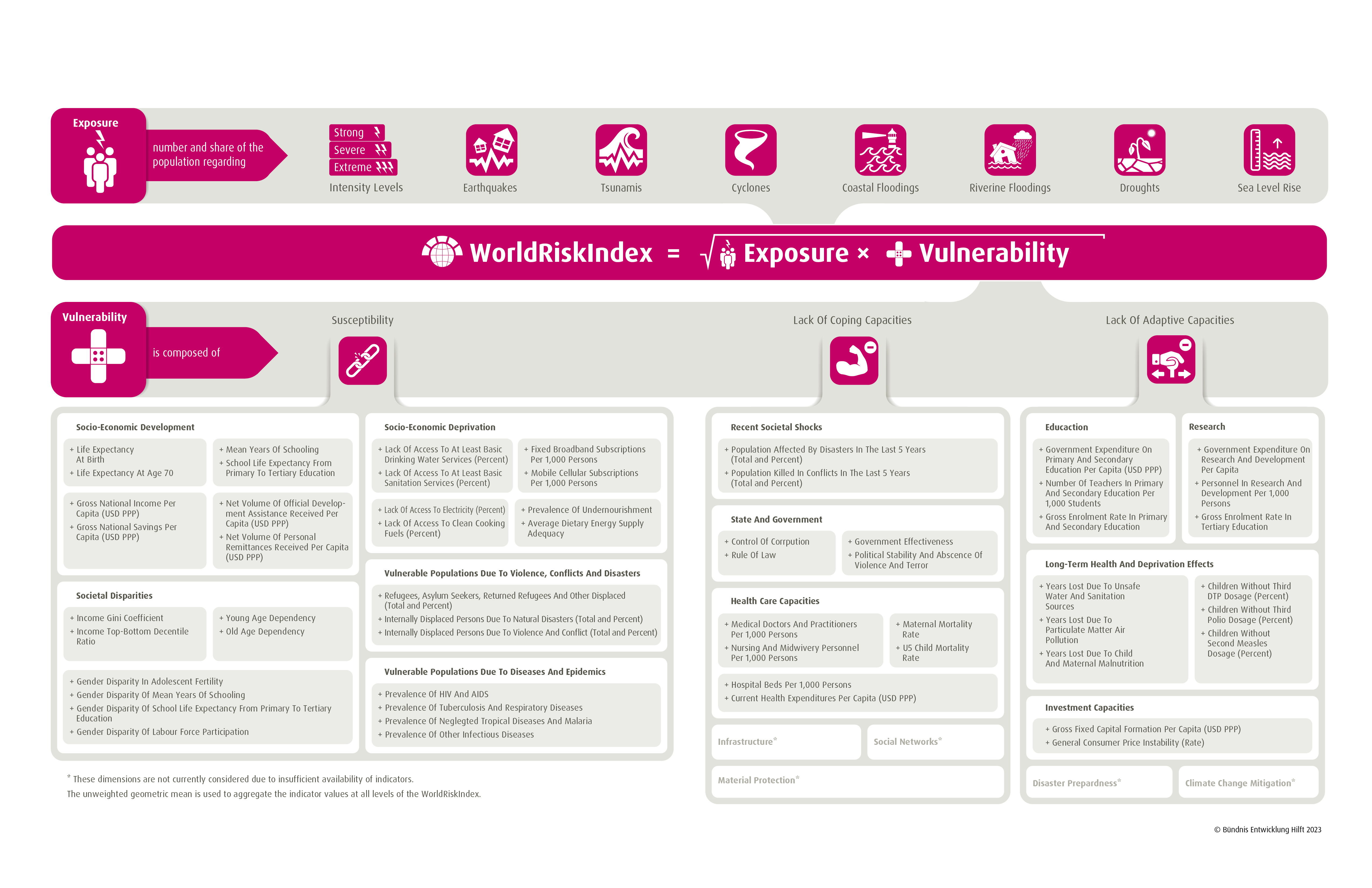

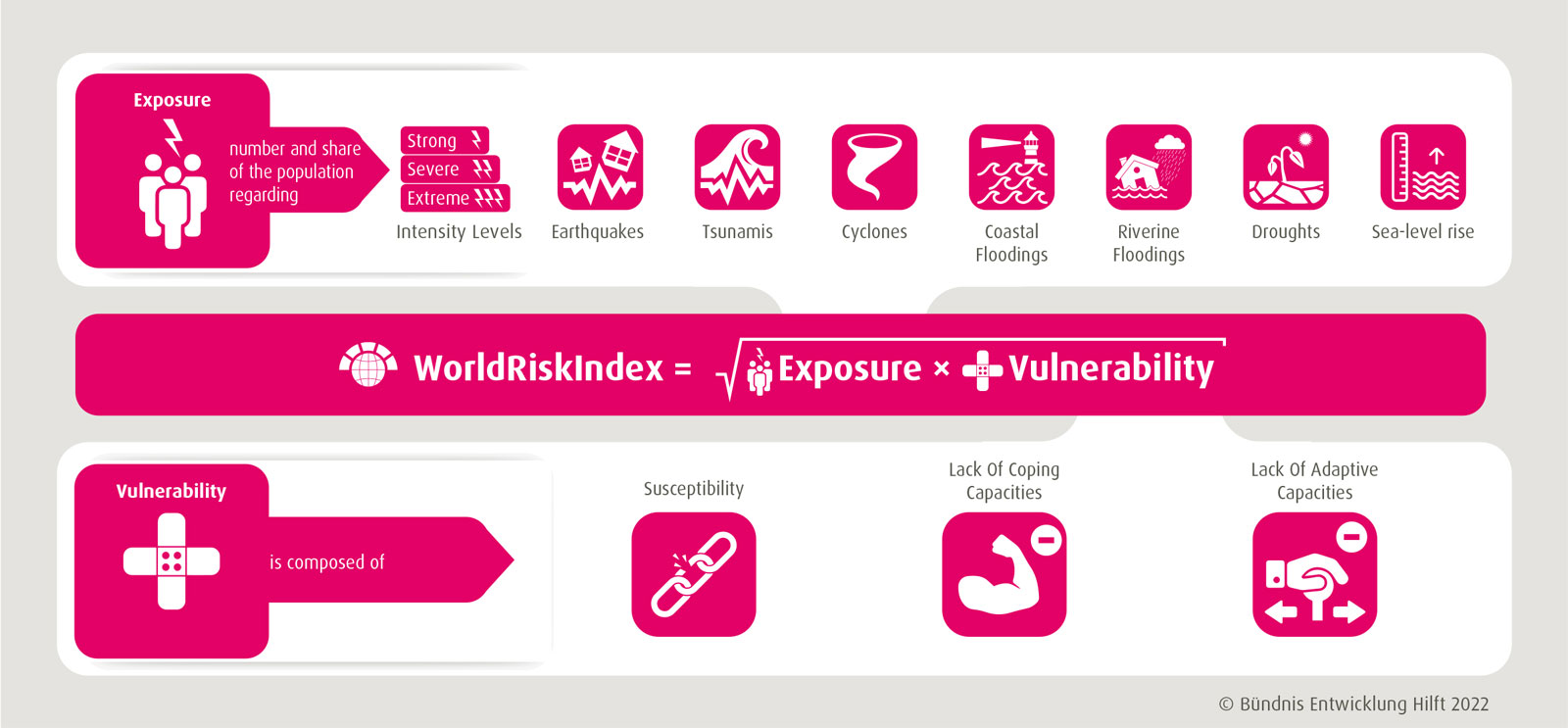

The WorldRiskIndex indicates the disaster risk from extreme natural events and negative climate change impacts for 193 countries in the world. It is calculated per country as the geometric mean of exposure and vulnerability. Exposure represents the extent to which populations are exposed to and burdened by the impacts of earthquakes, tsunamis, coastal and riverine floodings, cyclones, droughts, and sea level rise. Vulnerability maps the societal domain and is composed of three dimensions:

- Susceptibility describes structural characteristics and conditions of a society that increase the overall likelihood that populations will suffer damage from extreme natural events and enter a disaster situation.

- Coping involves various capacities and actions of societies to counter negative impacts of natural hazards and climate change through direct actions and available resources in the form of formal or informal activities, and to minimize damage in the immediate aftermath of an event.

- Adaptation, in contrast to coping capacities, refers to long-term processes and strategies to achieve anticipatory changes in societal structures and systems to counter, mitigate, or purposefully avoid future adverse impacts.

The basic model of the WorldRiskIndex with its modular structure, was developed jointly with the United Nations University Institute for Environment and Human Security (UNU-EHS). Since 2018, the Institute for International Law of Peace and Armed Conflict (IFHV) of Ruhr-University Bochum has taken over the calculation and continuously refined the model conceptually and methodologically. In 2022, the WorldRiskIndex is published with a completely revised model that includes 100 indicators from globally available and publicly accessible databases. For the first time, all 193 member states of the United Nations are represented. Among other things, the WorldRiskIndex serves as a guidance for decision makers and identifies fields of action for disaster risk reduction.

Calculation of Risk

Topic overview

Digital transformation is now influencing our lives in extensive ways – it’s hard to imagine our personal and professional lives without digital tools. Similarly, digital technologies have found their way into disaster management, creating new opportunities in both preparedness and response. The rapid proliferation of mobile devices means that those affected by a crisis are much easier to reach and much better informed; new technologies can assist with damage analysis and post-disaster needs assessment; and the increasing availability of data means that forecasting and early warning systems are becoming more accurate, allowing crises to be better prevented. In addition, digital technologies serve as important tools in the fight against hunger, poverty, and social inequality, as well as for improved health care and educational opportunities, and consequently for sustainable development and reduced vulnerability.

At the same time, the increasing use of, and thus dependence on, digital technologies bring challenges and risks. Digital infrastructure is vulnerable to damage from extreme natural events, personal data about aid recipients can be more easily misused, or digital disinformation can undermine protective measures in the event of a disaster. In addition, access to digital technologies is not ensured for all. The digital divide, if not addressed, can lead to overlooking affected people and further entrenching power imbalances. For sustainable disaster management, it is essential that careful consideration is given to the areas in which digital technologies add value. There is still much to be done to make digitization more sustainable, local and socially equitable, and to fully exploit its potential for disaster management.

Social protection systems protect people against various social risks – for example, by providing financial security in case of illness, accidents, unemployment, or old-age. In addition, social protection provides access to essential goods and promotes opportunities in challenging life situations, for example, through maternity benefits and family benefits.

Particularly in the context of crises and disasters, social protection systems are key instruments for protecting people against societal risks. Through state-led, private, and informal protection benefits, people can be protected from acute need, hunger, and poverty, and social inequality can be reduced.

To date, however, appropriate social protection is only accessible for a limited number of people worldwide. Especially in hotspot regions of disaster risk, comprehensive and equitable protection systems are crucial. The increasingly noticeable impacts of climate change, as well as the Covid-19 pandemic, underline the need to further expand and further integrate social protection systems into disaster preparedness and climate change mitigation and adaptation measures.

People fleeing their homes bear high risk

Extreme natural events such as floods or storms, political persecution, armed conflicts – these are just some of the many causes that force millions of people around the world to leave their homes. The reasons for migration and forced displacement are highly complex – their analysis shows how unevenly the risk of displacement and the risks during migration are distributed worldwide.

Refugees and displaced persons are also particularly in need of protection, which has been clearly demonstrated by the Covid-19 pandemic. Humanitarian aid has become more difficult, social distancing and hygiene measures can hardly be realized during the process of displacement or in many emergency shelters.

Political action must focus more on the needs of refugees and put their protection in the foreground. Not only does this include the compliance with international human rights but also the willingness of the international community to effectively implement international treaties, where climate action must be at its core. This is the only way to prevent people from having to leave their homes as a result of climate-related damages and thus losing their livelihoods

Disasters endanger water security

Until today, access to sufficient clean and safe water varies widely around the world, with the poorest often having to pay the most. Water shortages do not only affect a country’s agriculture and health care, also important development processes fall short when children are sent to fetch water instead of going to school. Extreme natural events and the effects of climate change intensify water-related problems as they push long-established water supply processes to their limits.

Therefore, providing water security means two things: on the one hand, guaranteeing people access to water supply, and on the other hand, protecting people from the dangers of water. In disaster situations, ensuring a secure water supply often becomes even more difficult than in times of non-crisis.

The international community thus faces major challenges if it is to meet Sustainable Development Goal 6, which is to guarantee all people worldwide universal access to clean and affordable water by 2030. However, rapid and consistent action is indispensable in order to counteract the multiple impacts of water scarcity and to increase the resilience of societies to disasters.

Children are especially vulnerable

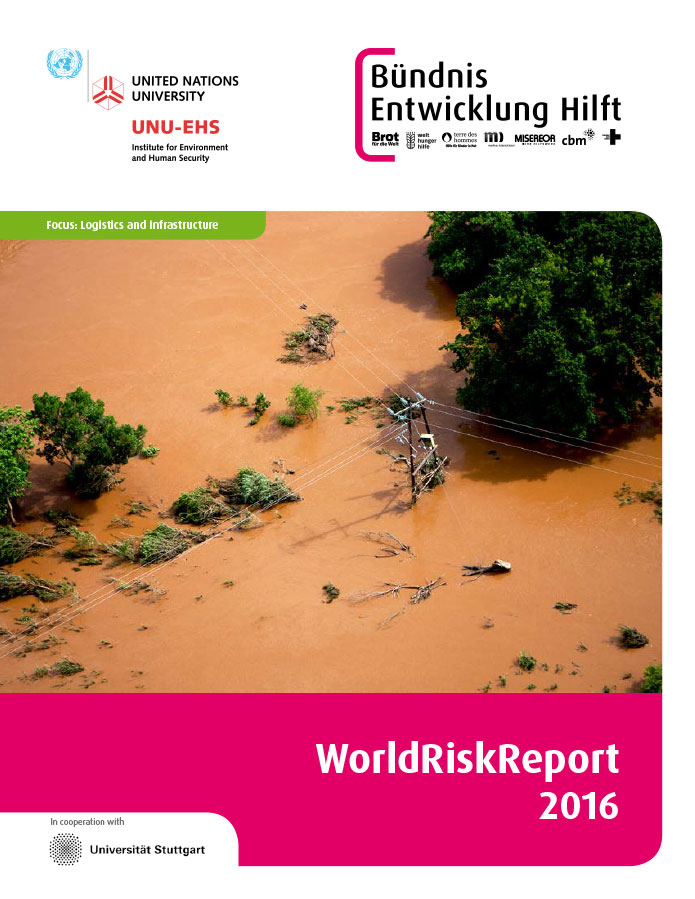

The prevailing conditions of logistics and infrastructure have a crucial impact on whether an extreme natural event leads to a disaster or not. Fragile infrastructure, such as dilapidated buildings, can have grave consequences because they pose a direct threat for the local population. Moreover, it delays the effective potential for those affected to help themselves and impedes humanitarian relief provided by the local authorities or from abroad. The difficulties that relief agencies face are mostly on the “last mile” of the logistics chain: Organizing transportation despite ruined roads or bridges, and ensuring fair distribution when, for example, there is a scarcity of water, food and shelter.

Information technology like the Internet, mobile phones or more recent technology such as drones or 3D printers, can support humanitarian logistics – that is, if they have not been impaired by a collapsed local infrastructure. But technology-based solutions aside, there still remains a host of challenges: examples include supporting self-help measures, coordinating the involved actors, making use of local resources, and the controversial issue of cooperation with the private sector and armed forces.

Risk in a state of flux

Risk is not static but a dynamic phenomenon, which is influenced by an array of environmental and societal factors. Until recently, humans were rarely the direct cause of extreme natural events. But as a result of their interference in the environment, they have increased the potential threat massively. The destruction of mangrove forests and coral reefs has reduced levels of protection against tidal waves and flooding. The clearing of mountain forests intensifies the rate of soil erosion and, consequently, the scale of flooding. Climate change and the increasingly frequent occurrence of “climate extremes” exacerbate this threat on an ongoing basis and increase the vulnerability of societies.

Countries can, however, develop and implement strategies and measures to protect themselves from the impacts of extreme natural events and thereby limit the extent of damage. As a general rule, the following applies to the risk level of all countries: A nation that possesses sufficient financial resources and functioning national and civil-societal structures, that confronts recurring natural events with an adaptive strategy and that is prepared to invest in measures to adapt to changing conditions such as weather and climate extremes, will be less adversely impacted by natural events.

Challenges until last mile

The prevailing conditions of logistics and infrastructure have a crucial impact on whether an extreme natural event leads to a disaster or not. Fragile infrastructure, such as dilapidated buildings, can have grave consequences because they pose a direct threat for the local population. Moreover, it delays the effective potential for those affected to help themselves and impedes humanitarian relief provided by the local authorities or from abroad. The difficulties that relief agencies face are mostly on the “last mile” of the logistics chain: Organizing transportation despite ruined roads or bridges, and ensuring fair distribution when, for example, there is a scarcity of water, food and shelter.

Information technology like the Internet, mobile phones or more recent technology such as drones or 3D printers, can support humanitarian logistics – that is, if they have not been impaired by a collapsed local infrastructure. But technology-based solutions aside, there still remains a host of challenges: examples include supporting self-help measures, coordinating the involved actors, making use of local resources, and the controversial issue of cooperation with the private sector and armed forces.

Disasters endanger global “Zero Hunger”

The international community aims to end all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030. To achieve this goal there is still a lot of work to do. In many countries disasters, wars or political instability in the past have been the main driver of increased vulnerability and food insecurity.

Disasters can have devastating impacts on a country’s food security – not only in the short term, but also long after they have occurred. According to the World Food Programme, the agrarian sector is especially affected by extreme natural events. They destroy harvests, stocks, and transport routes, and therefore above all the livelihoods of those depending on agriculture. In addition the frequency and extent of these natural food security risk factors are more and more aggravated by climate change. However, the reverse is true as well. It is not unusual for extreme natural events to turn into disasters because the population affected is particularly vulnerable due to a poor food situation. In the worst case, the combined effect of disasters and food insecurity leads to a fatal downward spiral, with the people hit slipping from one crisis into the next. Hence, a world without hunger would mean fewer disasters.

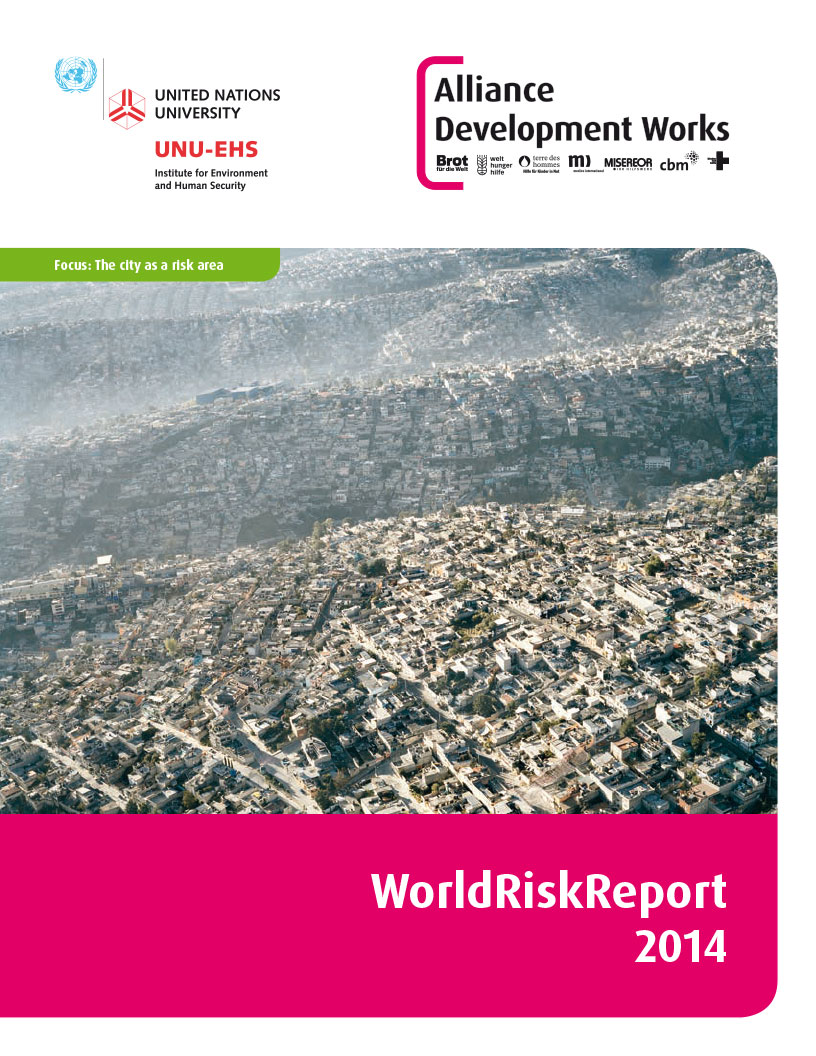

Chances and Challenges of urbanization

Urbanization is one of the megatrends of our times – and as such it bears a vast complexity. While the pull of the cities often creates problems for rural regions in the industrialized countries, massive urban population growth is posing great challenges for the metropolises in many countries of the Global South. For often enough, the growth of cities exceeds the capacity of authorities to develop and maintain adequate social and physical infrastructure. One of the most pressing results is the formation of marginal settlements in which urban dwellers lack basic civil rights and often compete for ill-paid jobs and low food availability. They are especially vulnerable towards natural hazards.

But urbanization does not produce exclusively negative effects on vulnerability, it can also create new chances for strengthening coping and adaptive mechanisms. In principle, the high density of buildings and other infrastructure in cities allows for an efficient implementation and operation of protective measures such as dyke systems or pumping stations. At the same time, cities concentrate large numbers of people, putting them into direct reach of central disaster management facilities such as ambulance services or fire brigades. Given the thematic focus “The city as a risk area”, the WorldRiskReport 2014 separately assesses the risk for urban areas.

Critical interaction between disasters and poor health care

Whether it be drought, cyclone, earthquake or floods, when an extreme natural event hits a village or a town, the vulnerability of the society crucially depends on the population’s health status as well as the health care and it’s functioning in crisis and disaster situations. But in times of the global financial crisis, the health systems worldwide are being subjected even more strongly to economic principles. Often humans facing an already unacceptable vulnerability suffer the most from these austerity and privatization measures.

However, the causal link works both ways. Not only do health and healthcare determine the disaster risk, but disasters have a negative impact on a society’s state of health if they overstrain or undermine the prevailing structures for the provision of care in its healthcare system. Futhermore, extreme natural events can cause direct health problems like heart and circulation problems and contribute to an increase and spread of disease carriers. A comprehensive approach to strengthening health systems and care therefore shows to be indispensable for disaster preparedness and response.

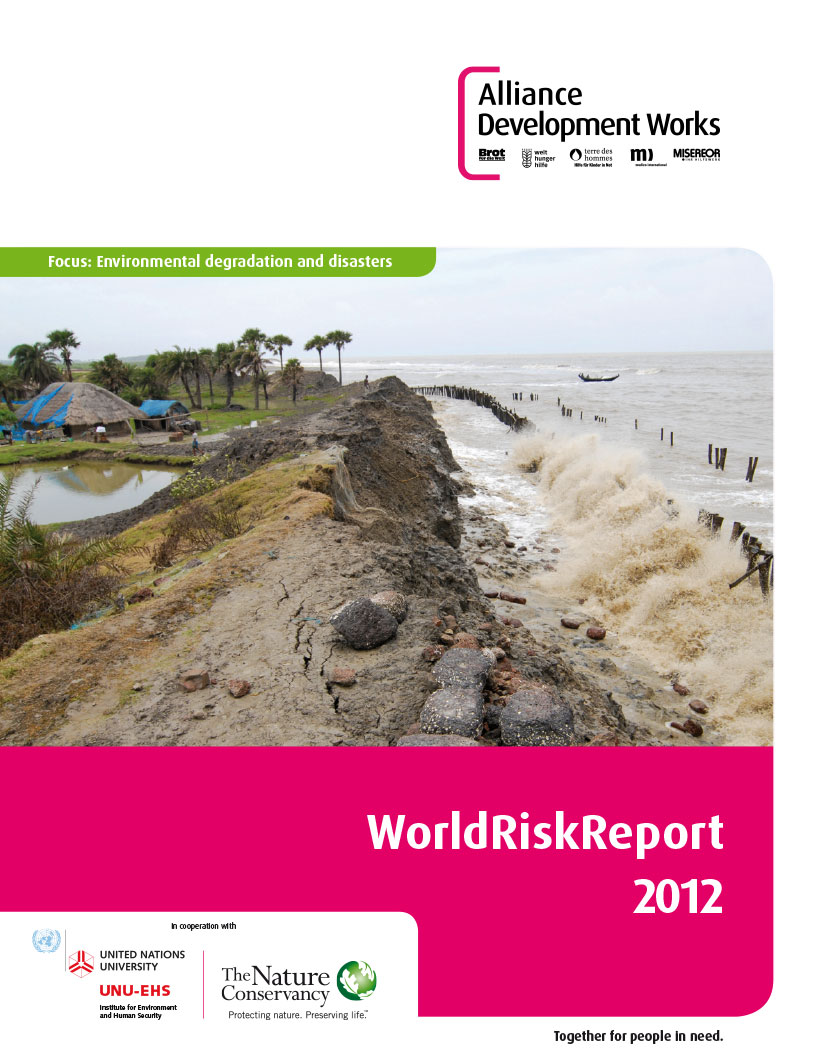

Functioning ecosystems as natural resilience factor

Intact ecosystems like for example forest and riparian wetlands or mangroves can significantly reduce disaster risk by reducing the susceptibility towards extreme natural events. They contribute to nutrition, income and wellbeing. In addition to food, they can also provide medicine and building materials, or they can represent new sources of income, for example via eco-based tourism. Meanwhile extreme natural events can have considerable effects on the environment and cause damage for ecosystems. Cyclones can pull over thousands of trees and destroy coral reefs or floods can contribute to erosions and damage solum.

In turn, the destruction of the environment and its natural protective function in pursuit of economic interests increases the risk of disaster in the wake of extreme natural events. Flooded coastal villages and washed away beaches whose natural protective belt of mangroves has been chopped down are just some examples among many others. This interaction between environmental destruction and disasters still gets too little attention by politics and science. Environmental protection and a sustainable handling of the environment should be strengthened from the local to the global level and included in disaster preparedness.

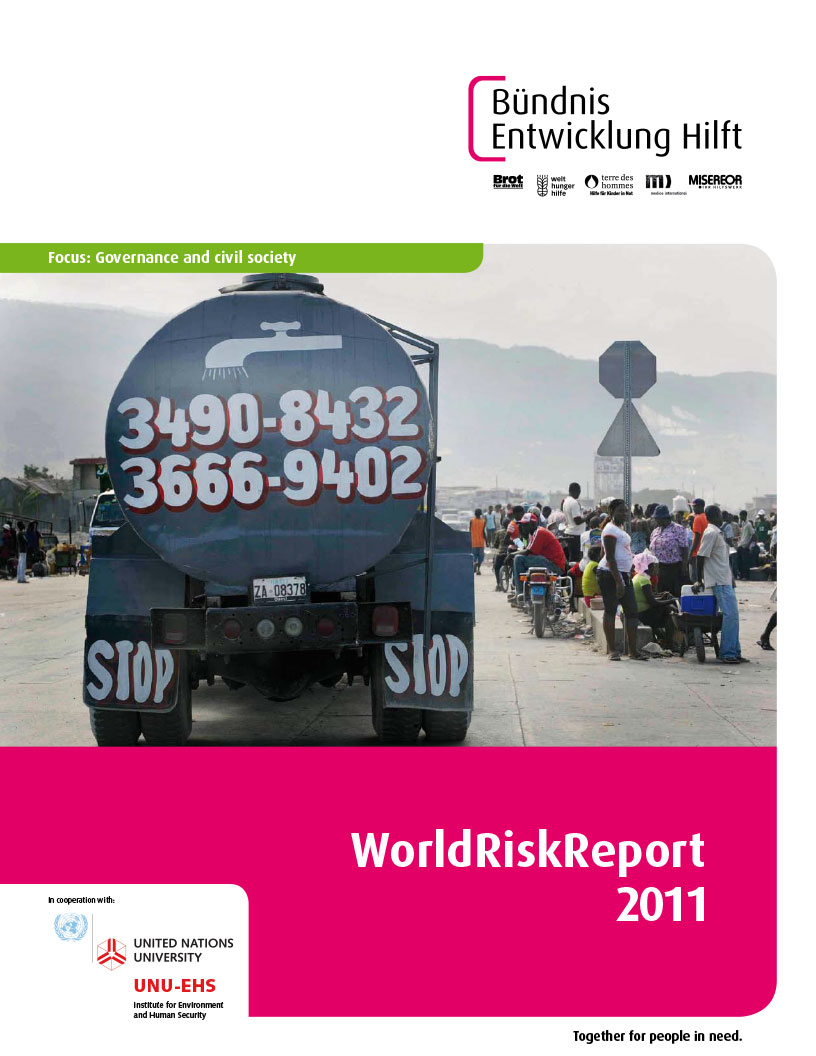

Fragile statehood as a risk driver

Humans can only influence to a limited degree, whether and with what intensity, natural events are to occur. But states can considerable influence the extent of a disaster by their governance in disaster preparedness and response. Especially states of weak governance are often not able to implement consistent strategies and measures and maintain mechanism to reduce the disaster risks. The development of disaster preparedness plans is often prevented by the low qualification or sheer non-existence of state personnel The vulnerability of the population towards extreme natural events is consequently high.

The relief aid and development work faces immense challenges, given the coincidence of weak governance and extreme natural events. In the complex interaction between governance and disasters, civil society can play an active role by demanding responsible and effective state policies and starting initiatives for disaster risk reduction. Nevertheless it is certain that both government and local civil society play a crucial role in disaster preparedness and that each must be strengthened accordingly.